Parashat Matot-Masei – 5785

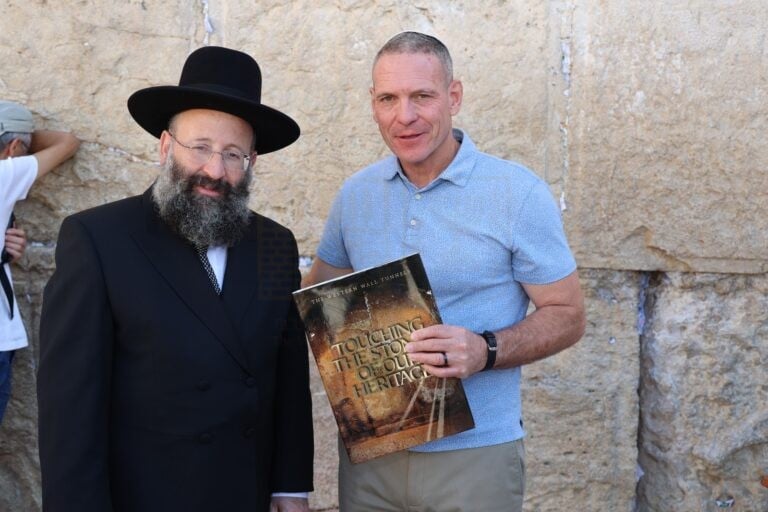

Rabbi Shmuel Rabinowitz, Rabbi of the Western Wall and Holy Sites

This Shabbat, we read two Torah portions: Matot and Masei. In Matot, we learn a profound lesson—one of the foundations of Judaism.

It takes place after the plague that struck the Israelite camp due to the sin with the daughters of Moab and Midian. Moses is commanded to take vengeance against Midian immediately, before he passes away from this world. But in practice, that is not what Moses did. He instructed Pinchas to lead the war of vengeance.

This seems puzzling. How could Moses deviate from G-d’s explicit command to “Take vengeance” (Numbers 31:2), which clearly implies that he himself should carry it out? Why didn’t he do it personally?

We find an explanation in the commentary of Rabbeinu Bechaye (Bahya ben Asher ibn Halawa, 1255–1340), a student of the Rashba and a brilliant Torah scholar and Kabbalist from Saragossa, Spain:

“But Moses, who had grown up in Midian and sat by its well, did not go. This is the meaning of the saying: ‘Do not throw a clod into the well from which you have drunk’.”

Moses, who brought the Torah and the commandments and knew more than any other human what G-d’s will was and how to fulfill it, understood that when G-d told him to “take vengeance” on a nation whose land had once sheltered him when he fled Pharaoh, it did not mean he should do so personally. Rather, he was to carry it out through a messenger.

Moses, the father of the nation, paved a path for generations to come: Nothing justifies an act of ingratitude. Ingratitude is never warranted in any situation.

This isn’t the first time Moses refrained from performing a divine task out of a sense of hakarat hatov—recognition of good. In the Exodus narrative, we find Moses refraining from striking the water and the earth, instructing Aaron to do so instead. As our sages taught:

“G-d said to Moses: The water protected you when you were cast into the Nile, and the earth sheltered you when you killed the Egyptian. It is not fitting that they be struck by your hand—therefore, they were struck by Aaron.”

Gratitude is a core value in Judaism. It is no coincidence that the Midrash uses language that may sound radical or extreme—but it is true, and proven by reality:

“One who did not know Joseph”—anyone who denies the kindness of a fellow human will eventually deny the kindness of G-d. As it says, “Who did not know Joseph,” and later that same Pharaoh said (Exodus 5), “I do not know the Lord.”

(As cited by Rabbeinu Bechaye in the name of the Midrash.)

Pharaoh, who during the famine in Egypt revered Joseph—who had, through his wisdom, brought salvation—and even praised the G-d who gave him such insight, later “forgot” Joseph’s kindness. And having done that, he soon after denied the greatness of G-d Himself.

Ingratitude is a trait that corrupts the soul. That is why the Torah despises it so strongly. This is also why the Torah commands: “Do not abhor an Egyptian, because you were a stranger in his land” (Deuteronomy 23:8). Rashi explains: “Even though they cast your male children into the Nile—why still not hate them? Because they gave you shelter in your time of need.” We are commanded to show gratitude even to the Egyptians. Despite the immense suffering they caused, in the end, Egypt was a place where we found refuge.

The Torah teaches us that gratitude—even toward those who later caused us harm—is a moral imperative. Moses, the greatest of prophets, taught us through his actions that recognizing kindness—even from imperfect sources—is a sacred duty. In a world often quick to forget, Judaism reminds us: we must never allow ingratitude to take root in our hearts. For one who denies the good of others risks forgetting the goodness of G-d Himself. Let us strive to live with eyes that remember and hearts that give thanks.