|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Parashat Behar 5784

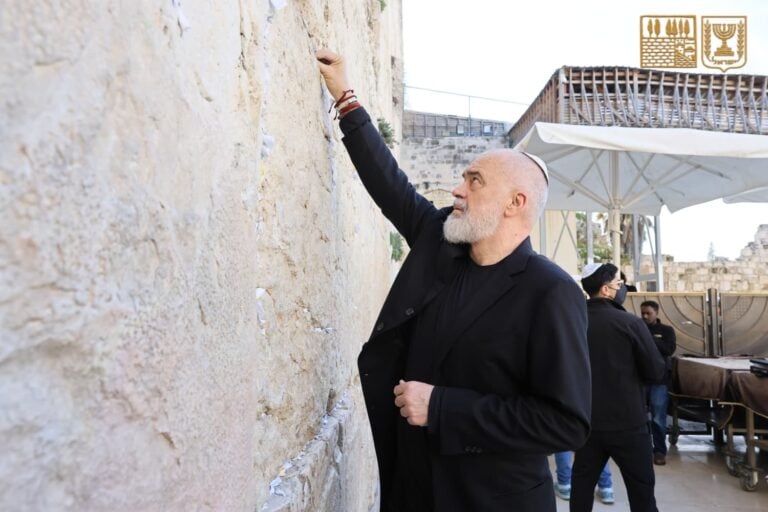

Rabbi Shmuel Rabinowitz, Rabbi of the Western Wall and Holy Sites

The relationship between the people of Israel and G-d is illustrated scripturally through several metaphors: the relationship of a father and his son, the relationship of a king and his people, and even romantic relationships between a man and a woman. Each of these metaphors appears in specific contexts, not by chance. For example, the Song of Songs is based on the metaphor of a romantic relationship, describing the historical processes that the people of Israel went through in their relationship with G-d over the generations, to illustrate the foundation of love and the covenant that persists in every situation. Meanwhile, when G-d sent Moses to Pharaoh, the king of Egypt, to command him to release the Israelites from slavery, He used the metaphor of a father and son: “My firstborn son, Israel” – a metaphor expressing commitment, responsibility, and concern.

However, there is another, relatively rare metaphor that appears only once in the five books of the Torah. This is the metaphor of master and servants. On the surface, this metaphor, especially to a person of the 21st century, may not seem appealing at all. This metaphor appears in this week’s portion, Behar, and it is worth examining why it appears specifically in this portion.

Firstly, it should be noted that the fact that this metaphor appears only once in the Torah indicates that this is not the religious motivation we should aspire to. G-d did not declare at Mount Sinai, “I am the Lord, your Master,” but rather “I am the Lord your G-d who brought you out of the land of Egypt, out of the house of slavery” – I am the G-d who cared for you, treated you well, and redeemed you, as stated in several verses beforehand: “You have seen what I did to the Egyptians, and how I bore you on eagles’ wings and brought you to Myself.” The appropriate religious motivation is for a person to feel gratitude to G-d for the kindness and abundance He has bestowed upon them. Nevertheless, the metaphor of master and servants does exist, but in what context?

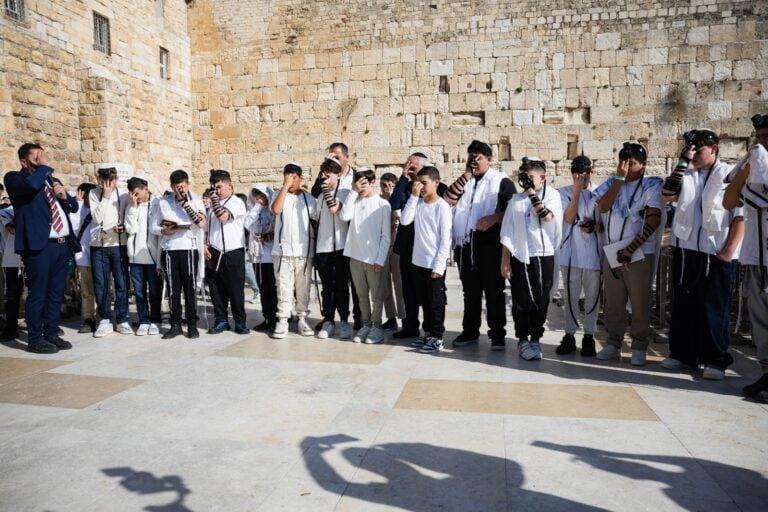

This week’s portion primarily deals with two commandments: Shmita, the Sabbatical Year, and Yovel, the Jubilee. The Sabbatical Year occurs in the land of Israel every seventh year. In this year, the agricultural obligation is to leave one’s land fallow and open it to everyone – to humans as well as to animals. The produce grown in this year is considered holy and designated for consumption only. The Jubilee commandment is similar to the Sabbatical Year: every fiftieth year, the agricultural obligation in the land of Israel is to leave one’s land as in the Sabbatical Year. However, in the Jubilee year, the egalitarian aspect extends to two additional areas.

The first area is the redemption of lands. In ancient Israel, a person sat on the land inherited from their ancestors and did not sell it to another person unless they encountered severe economic difficulties. In the Jubilee year, all sold land returns to its original owners. Thus, the economic reality returns to its original state, where every person has land inherited from their ancestors and sustains themselves from it.

The second area in which the egalitarian aspect is expressed in the Jubilee year is regarding servants. A person who was sold into slavery never did so willingly. However, the phenomenon of slavery did not only exist as a result of the despicable trade of slaves. There were those who fell into such dire straits that they preferred to sell themselves into slavery as long as they could survive. In the Jubilee year, all Israelite slaves go free and return to their families and homes as free people. Thus, the Babylonian Talmud describes the beginning of the Jubilee year:

From Rosh Hashanah until Yom Kippur [of the Jubilee year], the slaves eat and drink and rejoice, and their crowns are on their heads. Once Yom Kippur arrives, the court blows the shofar, and the slaves are dismissed to their homes.

(Tractate Rosh Hashanah, page 8)

The reason that the Torah gives for the release of the slaves in the Jubilee year is this:

For they are My servants, whom I brought out of the land of Egypt; they shall not be sold as slaves!

(Leviticus 25:42)

G-d stipulates that we are His servants – only to release us from the yoke of another person. Servitude to G-d is not degradation; it is the path to freedom! When we recognize that we are all G-d’s servants, we understand that we do not have the right to dominate others. When we internalize our servitude to G-d – true equality among human beings can be achieved.